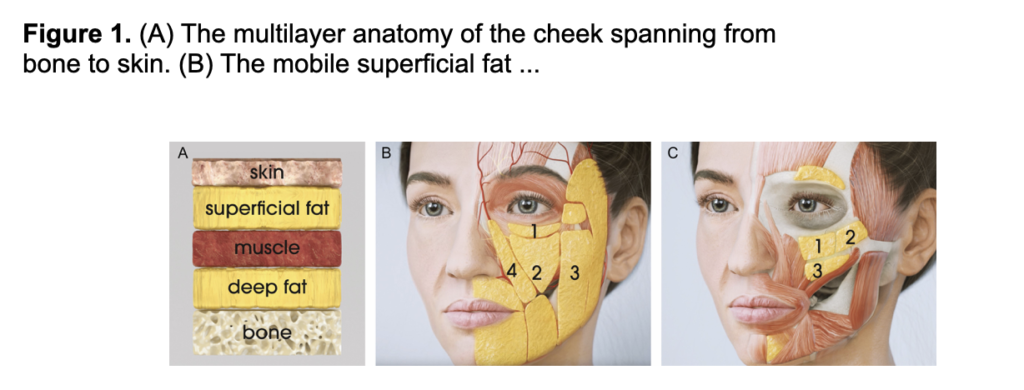

To optimize procedural safety and achieve natural-looking results, injectors attempting to correct midface volume deficiency should master the 3-dimensional anatomy of this area. A key anatomical concept is the 5-layered arrangement of this region, spanning from bone to skin and featuring deep static fat compartments separated from superficial mobile fat pads by a thin muscular layer (Figure 1A). Understanding how aging affects each of these layers is also essential to restore a youthful appearance without resulting in an exaggeratedly full face.1 Finally, awareness of anatomical dangers represented by neighboring vascular structures must guide the physician’s choices regarding injection technique, depth, as well as pre- and posttreatment precautions.

(A) The multilayer anatomy of the cheek spanning from bone to skin. (B) The mobile superficial fat compartments: 1, infraorbital fat compartment; 2, medial cheek fat compartment; 3, middle cheek fat compartment; 4, nasolabial fat compartment. (C) The static deep fat compartments: 1, medial sub-orbicularis oculi fat; 2, lateral sub-orbicularis oculi fat; 3, deep medial cheek fat (medial and lateral deep medial cheek fat).

Superficial Fat Compartments

Immediately deep to the dermis, superficial fat compartments of the midface constitute a dynamic soft tissue layer moving along with the underlying muscles (Figure 1B). Through connective tissue fibers rising upwards to the dermis, superficial fat pads provide a strong attachment of the skin to the muscles. There are essentially 4 superficial fat pads that contribute to midface aging through changes in volume distribution: the infraorbital fat compartment (IOF), the medial cheek fat compartment (MCF), the middle cheek fat compartment (MiCF), and the nasolabial fat compartment (NLF).

The IOF is bound superiorly by the superficial extension of the orbicularis retaining ligament (ORL) and the inferior eyelid and connects with the MCF inferiorly. Atrophy of the IOF during aging causes the bony appearance of the lateral side of the orbital rim and may worsen tear trough deformity.

The MCF occupies the middle portion of the cheek where it overlies the lateral part of the deep medial cheek fat (DMCF). Over time, MCF atrophy may accentuate the depth of the mid-cheek concavity and the appearance of the mid-cheek groove, contrasting with the increased fullness of the nasolabial fat.

The MiCF bounds medially with the MCF, laterally with the temporal cheek fat, and superiorly with the superficial extension of the zygomatic cutaneous ligament (ZCL). Aging of the MiCF primarily results in volume loss, which accentuates the depression of the MCF.

Finally, the NLF is the most medial superficial fat compartment of the midface. This rectangular fat pad bounds medially with the nasal sidewall, the levator labii superior alaeque nasi muscle, and the nasolabial septum, and laterally with the medial cheek septum, the IOF, and the MCF. Compared with its neighboring fat compartments, the NLF increases in width and collapses inferiorly over time, resulting in pronounced nasolabial folds and nasojugal grooves in older patients.

Facial Muscles and Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System

The superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) is essential in creating facial expression through transmission of the muscles’ contraction to the skin. Because superficial fat pads are intricately connected to the underlying muscle layer, the dynamism of this area should be well-understood when filling the superficial fat to avoid any unwanted lumpy appearance on muscle activation, for example, when smiling.

Located just beneath the superficial fat compartments, this soft tissue layer includes both facial muscles and ligament-like tissue. Three laminae form the aponeurosis: (1) the thin fascia on the outer surface of muscles, (2) the mimetic muscles, and (3) the thicker fascia on the underside of muscles. Fasciae 1 and 3 fuse in the absence of muscles.

In the midface region, the orbicularis oculi muscle (OOM), the levator labii superioris, the levator labii superior alaeque nasi, the zygomaticus minor and major, the depressor anguli oris, the platysma, and the risorius constitute the superficial layer of facial muscles. The levator anguli oris muscle and the buccinator constitute the deeper layer.

Deep Fat Compartments

In the midface, 3 deep fat compartments adhere to the bone and provide structural support to the overlying soft tissue layers (SMAS and superficial fat). Atrophy of these compartments thus leads to deflation of the upper cheeks during aging (Figure 1C).

Recent anatomical studies found the deep sub-orbicularis oculi fat to be systematically divided into 2 separate compartments: medial and lateral. The medial sub-orbicularis oculi fat (mSOOF) is a triangular fat compartment extending from the lateral canthal line onto the maxillary bone. It is separated from the lateral SOOF by a vertical septum, and from the inferior eyelid’s pre-septal space by the ORL. Inferiorly, the mSOOF also connects with the medial ZCL. Finally, the deep fascia of the OOM cover the mSOOF and create a “hermetic” cover fusing with surrounding ligaments. The lateral sub-orbicularis oculi fat (lSOOF) lies laterally to the vertical septum and covers the prominence of the zygomatic bone, meeting with the temporal fat laterally. The lateral ZCL and the buccal fat pad constitute its inferior border. Although some interpretations of the periorbital anatomy differentiate the SOOF from a deeper pre-periosteal fat, published anatomical evidence, as well as the authors’ own observations, mostly support the idea of the SOOF directly adhering to the bone.

Finally, underneath the superficial MCF and the SMAS, the triangular-shaped DMCF directly overlies the maxillary bone. The DMCF is occasionally represented as 2 compartments (medial and lateral DMCF) partitioned by the levator anguli oris.

The nomenclature and location of the deep fat pads may vary throughout the literature, occasionally leading to discrepancies in recommended target injection areas. Our recommendation is to specifically target the deep fat compartments, that is, the mSOOF, lSOOF and/or DMCF (as appropriate depending on patient needs), which are directly affected by the aging process. In the following sections, the proposed treatment approach does not aim to fill spaces but rather to compensate fat atrophy and volume loss directly in the impacted areas.

Furthermore, because deep fat compartments have been shown to be relatively stable during aging (they are not displaced inferiorly onto the bone), deep filler implantation in these compartments and in contact with the bone will provide support for the overlying structures and increase anterior projection.

Ligaments and Septa

In the midface, the ORL and tear trough ligament, the ZCL, the buccal-maxillary ligaments, and the mandibular ligaments originate from the facial skeleton and pierce the SMAS to finally insert and spread into the dermis, thus qualifying as “true” retaining ligaments. With age, loosening of this ligamentous system may contribute to the gravitational descent of superficial tissues. Though the role of ligaments in facial aging has not been fully elucidated, weakening of the ORL may play a specific part in the formation of the tear trough deformity and palpebromalar groove.

Importantly, several pre-septal spaces permit the mobility of superficial tissue layers over deep ones and independent movements of the orbital and perioral portions of the superficial fascia: the pre-septal space of the lower lid is separated from the prezygomatic space by the ORL, in turn separated from the masticator space by the ZCL. These pre-septal spaces are generally exempt from blood vessels and nerves that pass through their boundaries, so the area is relatively safe for dermal filler injection.

Bone

With age, bone remodeling (resorption or augmentation) affects the facial skeleton at specific sites, thereby altering the location of all structures overlying the bone, that is, fat pads, ligaments, and muscles. Resorption of the superomedial and inferolateral aspects of the orbit contributes to the stigmata of periorbital aging, such as increased prominence of the medial fat pad, elevation of the medial brow, and lengthening of the lid-cheek junction (tear-trough deformity). In parallel, retrusion of the maxilla affects maxillary and pyriform angles, resulting in less support to the alar base and upper lip part of the nasolabial groove.

Citations:

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4174112/

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9373948/

[3] https://journals.lww.com/prsgo/fulltext/2013/12000/the_clinical_importance_of_the_fat_compartments_in.4.aspx

[4] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352647518300388

[5] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10541169/

[6] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jocd.14700